My Critique of Happy Valley

Happy Valley distinguishes itself within British crime drama by refusing the genre’s usual consolations; Sally Wainwright’s writing anchors procedural mechanics in lived grief and stubborn community integrity. The series’ central limitation is its unflinching portrayal of violence, which can feel punishingly visceral and, in earlier episodes, risks overwhelming the quieter humane studies it seeks to balance.

Yet Sarah Lancashire’s performance provides a steady moral centre, with the cumulative arcs across three series shaping a portrait of resilience rather than spectacle. Positioned alongside contemporaries like Broadchurch or Unforgotten, it is more insistently regional, less polished, and more exacting in its depiction of systemic neglect and coercive control.

For contemporary viewers, its matter matters: it interrogates the resilience of institutions and families alike, forging a blueprint for character-led drama rooted in a landscape too often caricatured.

Principal Characters & Performances

Sergeant Catherine Cawood

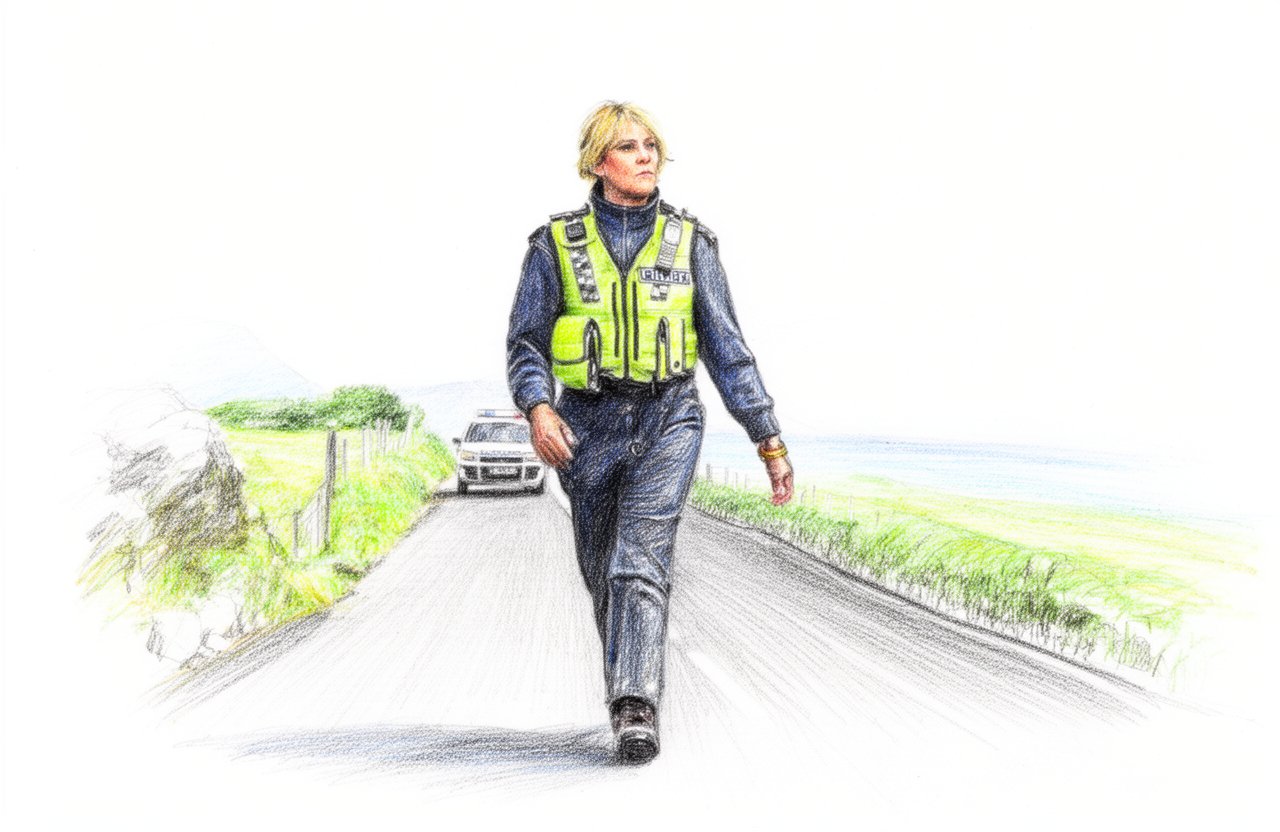

At the heart of Happy Valley is Sarah Lancashire’s Sergeant Catherine Cawood, a performance that redefined the police drama protagonist. Catherine is a woman defined by profound grief and unwavering duty.

She carries the trauma of her daughter Becky’s suicide, a tragedy she directly links to the manipulative cruelty of Tommy Lee Royce.

Her professional life in the Calder Valley police force is a daily grind against drug crime and domestic violence, met with a weary, pragmatic cynicism. Yet, this is layered with a deep, often furious compassion for the vulnerable.

Her personal life is equally complex, centred on raising her grandson Ryan, Becky’s son.

Lancashire embodies Catherine with a breathtaking physical and emotional authenticity. She conveys decades of hurt in a glance and a ferocious protective instinct in her stance.

The character’s brilliance lies in her contradictions: she is brutally direct yet deeply caring, emotionally scarred yet resilient, making her one of British television’s most fully realised and enduring figures.

Tommy Lee Royce

James Norton’s portrayal of Tommy Lee Royce provided the series with its chilling, magnetic antagonist. He is not a cartoon villain but a profoundly damaged and dangerous product of the same valley he terrorises.

Tommy is a manipulator and a narcissist, whose charm is a thin veil for a capacity for extreme violence.

His relationship with Catherine is the series’ core conflict, a toxic bond forged through the death of her daughter. Norton masterfully depicts Tommy’s escalating menace, from a released convict to a figure of inescapable threat.

What makes the performance particularly unsettling is the character’s moments of twisted vulnerability and his obsessive, possessive claim over Ryan.

This complexity ensures Tommy is never merely a plot device. He is the embodiment of the past’s relentless grip on the present, a ghost that Catherine cannot exorcise, making every appearance tense with historical and immediate danger.

Clare Cartwright and Supporting Pillars

Siobhan Finneran brings vital warmth and grounding as Clare Cartwright, Catherine’s sister. A recovering alcoholic, Clare provides both practical support in raising Ryan and emotional ballast for Catherine.

Their relationship, built on shared loss and sharp, loving humour, is the show’s essential heart.

It offers a domestic sanctuary against the professional chaos. Rhys Connah, as Ryan Cawood, delivers a remarkably nuanced performance, growing from a young boy to a teenager grappling with the difficult truth about his father.

The tension between Catherine’s love and her fear of Tommy’s influence over Ryan fuels much of the series’ later drama.

Notable Guest and Supporting Stars

Happy Valley’s tapestry is enriched by stellar guest turns. Steve Pemberton is tragically believable as Kevin Weatherill, the weak-willed accountant whose disastrous scheme triggers the first series.

His ordinary desperation makes the ensuing violence feel horrifically plausible.

Charlie Murphy portrays kidnap victim Ann Gallagher with a raw, resilient dignity. George Costigan embodies the entitled panic of her father, Nevison, while Joe Armstrong’s volatile Ashley Cowgill brings a gritty criminal threat.

Later series introduced compelling figures like Amelia Bullmore’s Vicky Fleming and Katherine Kelly’s DI Jodie Shackleton, expanding the show’s exploration of community and corruption. Each performance, no matter the screen time, feels authentically rooted in the world Sally Wainwright created.

Key Episodes & Defining Stories

Episode 1 (Series 1)

The pilot episode does not ease you in. It establishes the entire emotional and thematic landscape in one hour.

We meet Catherine Cawood on a grimly comic call about a drunken man, immediately showcasing her world-weary professionalism and the valley’s social problems.

The devastating news of Tommy Lee Royce’s release lands with the force of a physical blow, revealing the personal trauma underpinning her toughness. Parallel to this, we see the genesis of the kidnap plot through Kevin Weatherill, played by Steve Pemberton.

His meeting with Joe Armstrong’s Ashley Cowgill sets a fatal chain of events in motion. This episode matters because it masterfully braids intimate character tragedy with a ticking criminal conspiracy.

Fans remember it for its brutal efficiency, Sarah Lancashire’s commanding introduction, and the instant, palpable sense of a world where personal and professional hells are inseparable.

Episode 3 (Series 1)

This is the episode where Happy Valley declared its uncompromising nature. The harrowing abduction of PC Kirsten McAskill by Tommy Lee Royce and his accomplice is a sequence of pure, realistic terror that sparked significant public debate.

It removed any safety net, showing that violence here is sudden, ugly, and has lasting consequences. The kidnap plot involving Ann Gallagher intensifies, with Charlie Murphy’s performance conveying sheer survival instinct.

James Norton’s Tommy becomes an unequivocal monster here, yet one with a terrifyingly human rage. It’s a crucial turning point where the series’ tension becomes almost unbearable.

Fans remember it as the moment the show proved it wouldn’t flinch, cementing its reputation for gritty, psychological realism that prioritises impact over comfort.

Episode 6 (Series 3)

The series finale had the immense task of concluding a nine-year story, and it delivered with profound emotional intelligence. The long-awaited, final confrontation between Catherine and Tommy is not a grand action set piece but a raw, verbal showdown in a kitchen.

It’s a masterpiece of acting from Sarah Lancashire and James Norton, where years of pain, accusation, and twisted connection are laid bare. The resolution of subplots, like that of pharmacist Faisal Bhatti, reinforces the show’s consistent theme of moral compromises in a broken world.

Fans remember this episode for its perfect catharsis. It provides closure not through simplistic victory, but through exhausting, hard-won truth and the fragile hope of moving on.

It solidified Happy Valley’s legacy as a drama that valued character resolution as much as plot resolution.

The World of Happy Valley

The Calder Valley in West Yorkshire is not just a setting; it is a central character. The show’s title, derived from local police slang for the area’s drug problems, immediately frames this landscape of post-industrial towns and sweeping moorland as a place of contradiction.

Its beauty is undeniable, captured in cinematography that doesn’t shy from the grim weather, but it harbours a undercurrent of deprivation and crime. Filming in real locations like Hebden Bridge, Sowerby Bridge, and Mytholmroyd grounds the drama in tangible reality.

The cramped terraced houses, the rain-slicked streets, and the isolated farmhouses all contribute to a sense of claustrophobia, even amidst open spaces. This is a world where everyone is connected, where crimes ripple through close-knit communities, and where the past is never truly buried.

The environment is a constant reminder of the social pressures that shape the characters’ lives.

Origin Story

Happy Valley was created and written by Sally Wainwright, a writer renowned for her deep connection to Northern England. The BBC commissioned the series in late 2012, with the Red Production Company, a staple of British television drama, producing.

Filming began in the Calder Valley in November 2013, with directors like Euros Lyn and Tim Fywell helping to realise Wainwright’s vision. The score was composed by Ben Foster, and the title sequence perfectly set the tone with Jake Bugg’s “Trouble Town.” It premiered on BBC One in April 2014, quickly establishing itself as a major new voice in the crime genre.

Narrative Style & Tone

Happy Valley operates with a relentless, character-driven realism. It blends police procedural elements with deep domestic drama, ensuring the cases are always personal.

The dialogue is rich with Yorkshire vernacular, adding authenticity and rhythm.

The tone is fundamentally grim and psychologically acute, examining trauma, grief, and resilience without sentimentality. Yet, it is punctuated by flashes of sharp, often dark humour, usually through Catherine’s cynical asides.

The violence is graphic but never gratuitous; it is shown to have weight and consequence, haunting both victims and perpetrators.

The narrative frequently cross-cuts between different strands—police, criminals, families—building a comprehensive, tense portrait of a community in crisis.

How is Happy Valley remembered?

Happy Valley is remembered as a benchmark for British television drama. It garnered widespread critical acclaim, winning two BAFTA Television Awards for Best Drama Series and holding exceptional scores on review aggregators.

Its public impact was significant, with the first episode attracting over 8.6 million viewers and the finale becoming a national event in 2023.

Beyond ratings, its legacy is defined by Sarah Lancashire’s iconic performance, which has been ranked among the greatest in TV history. The show is praised for its unflinching look at social issues, its complex female protagonist, and its masterful synthesis of crime thriller mechanics with profound human emotion.

It demonstrated that regional stories with specific accents and landscapes could achieve universal resonance, influencing a wave of similarly gritty, location-anchored dramas. It is a show that respected its audience’s intelligence and its characters’ complexity.

In Closing

Happy Valley stands as a complete, powerful piece of storytelling. From its first moments to its last, it delivered a consistent, bruising, and ultimately cathartic exploration of justice, family, and survival against a vividly realised backdrop.