My Critique of Lovejoy

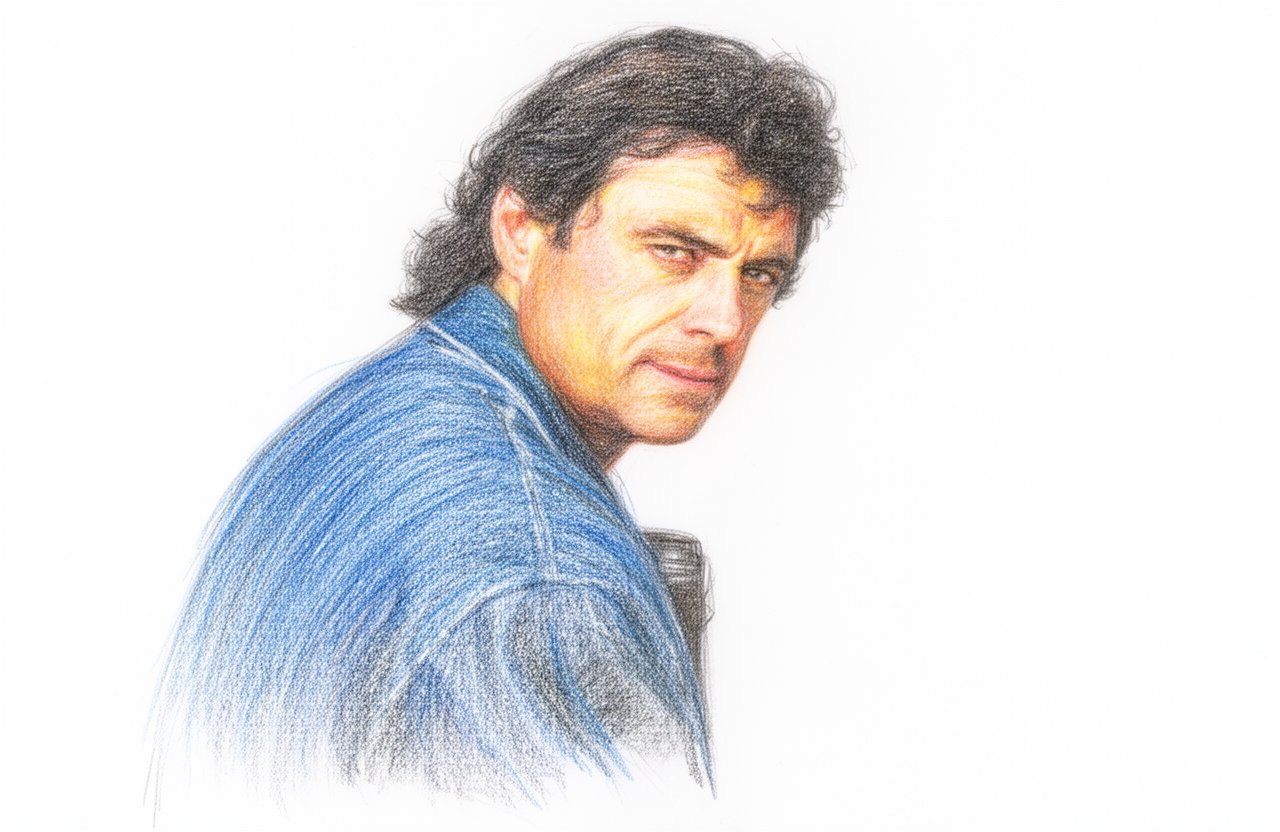

Lovejoy carved a singular niche by weaving intricate art-world procedurals around Ian McShane’s roguish charisma.

Episodes like The Judas Pair and Riding in Rollers elevate the format beyond cosy caper, treating forgery, restitution and market manipulation with substantive, credible detail. Yet the series’ charming cynicism can feel arch, its episodic churn and often superficial treatment of regional crime limiting deeper thematic bite; alongside contemporaries such as Inspector Morse or Cracker, it skews lighter, more escapist.

For modern viewers, its enduring appeal lies in a rare fusion of niche expertise, sly moral ambiguity and deft ensemble chemistry, though the dated pacing and occasional contrivance demand patience.

Principal Characters & Performances

Lovejoy

Ian McShane’s portrayal of the eponymous antiques dealer is the undeniable engine of the series. Lovejoy is a classic rogue, a self-described “divvie” with an almost psychic feel for genuine antiques.

He operates in the grey areas of the trade, often skirting the law to pull off a profitable deal or right a perceived wrong.

McShane brings a unique blend of charm, cynicism, and vulnerability to the role. His direct-to-camera asides create an intimate, conspiratorial bond with the audience.

We are let in on the scam, privy to his assessments of people and objects. This charm offensive is crucial, as it makes his frequent moral compromises palatable, even endearing.

He is not a hero in the traditional sense, but a pragmatist with his own code. His deep knowledge and respect for the history and craft of antiques often clash with his need to make a living, creating the central tension of his character.

McShane ensures Lovejoy is never a mere caricature of a wheeler-dealer, but a fully realised, flawed, and compelling guide to this niche world.

Tinker Dill

As played by Dudley Sutton, Tinker is Lovejoy’s loyal, rumpled, and perpetually thirsty associate. More than just a sidekick, Tinker is the bedrock of Lovejoy’s operation.

He is the repository of trade gossip, the keeper of contacts in pubs and back rooms, and a skilled craftsman in his own right.

Sutton’s performance is a masterclass in character acting. Tinker, with his scruffy appearance and fondness for a drink, could easily be a two-dimensional figure.

Instead, Sutton imbues him with a weary wisdom and an unwavering, if occasionally exasperated, loyalty to Lovejoy.

Their relationship is the show’s most consistent partnership, built on mutual need and deep, unspoken affection. Tinker is the anchor that prevents Lovejoy’s more outlandish schemes from floating completely away, and Sutton’s grounded presence provides a perfect counterbalance to McShane’s sharper energy.

Lady Jane Felsham & Charlotte Cavendish

Phyllis Logan’s Lady Jane Felsham represents the world Lovejoy both courts and subtly subverts. As an upper-class woman trapped in a sterile marriage, she finds excitement and purpose in Lovejoy’s adventures.

Logan brings grace and intelligence to the role, making Jane far more than a damsel or a patron.

She is Lovejoy’s moral compass at times, his entry into country house sales, and the source of a long-running, wistful romantic tension. Their relationship, built on genuine fondness and class difference, is a core emotional thread of the early series.

Later, Caroline Langrishe’s Charlotte Cavendish enters as a different kind of foil. A professional auctioneer, she is Lovejoy’s business partner and equal in the trade.

Langrishe portrays Charlotte as capable, sophisticated, and able to match Lovejoy’s cunning, introducing a more mature and professionally charged dynamic that shifted the show’s interpersonal landscape in its later years.

Eric Catchpole & Beth Taylor

The role of Lovejoy’s young assistant showcases the show’s evolution. Chris Jury’s Eric Catchpole, in the early series, is the audience surrogate: naive, eager, and often hilariously out of his depth.

His wide-eyed reactions to Lovejoy’s scams provide both comedy and a grounding perspective.

When Eric departs, Diane Parish’s Beth Taylor takes on a similar but distinct role. Beth is sharper, more streetwise, and less easily shocked, reflecting the show’s own progression.

Parish brings a lively, modern energy, and her character often challenges Lovejoy more directly, signalling a change in the workshop’s dynamics.

Key Episodes & Defining Stories

The Judas Pair

Adapted from Jonathan Gash’s award-winning debut novel, this episode is the series at its most atmospheric and morally complex. The hunt for a legendary, cursed pair of duelling pistols used in a modern murder pulls Lovejoy into a genuinely sinister plot.

It moves beyond light comedy into darker territory, exploring obsession and the lethal history objects can carry.

The mystery is tightly constructed, demanding Lovejoy use his skills as a divvie and a detective. It firmly establishes that the antiques world can be a backdrop for serious crime, not just charming cons.

For fans, it’s a cornerstone because it proves the show’s depth. It demonstrates that Lovejoy’s knowledge isn’t just for profit, but for uncovering truth, and it cemented the programme’s reputation as more than just a pleasant diversion.

The Italian Venus

This episode perfectly encapsulates Lovejoy’s fascination with class, injustice, and the art of the forgery itself. Asked by Lady Jane to help a disinherited artist, Lovejoy discovers the man is creating expert fake bronzes.

The plot becomes an elaborate sting against the greedy brother, using a supposedly lost Renaissance statue as bait.

Its brilliance lies in the detailed portrayal of the bronze-casting process, treating the creation of a forgery with as much respect as the authentic article. It highlights Lovejoy’s ambiguous ethics: he facilitates a fraud to achieve a fairer outcome.

Fans remember it for its clever, satisfying con and its thoughtful exploration of talent versus inheritance, all set within the beautiful, unequal world of the country house.

The Prague Sun

This ambitious episode breaks the show from its East Anglian confines, venturing into post-Cold War Czechoslovakia in search of a stolen diamond. It’s a historical snapshot, capturing the chaotic energy and opportunistic crime of the newly opened East.

Lovejoy and his team navigate a foreign landscape of murky officials and emerging markets.

The stakes feel different and higher, involving international borders and political change. It matters in the series arc as it tests Lovejoy’s skills on a global stage, showing his methods adapting to a wider, riskier arena.

Fans value it for its scope and ambition, proving the show could successfully transplant its formula into a geopolitically charged context while keeping its focus on provenance, greed, and the chase.

The World of Lovejoy

The series is rooted in the landscapes of East Anglia, primarily Suffolk and Essex. This is not a generic English countryside, but a specific, lived-in region.

Lovejoy operates from the historic antiques centre of Long Melford, with stories unfolding in villages like Lavenham and Finchingfield, their half-timbered houses and village greens providing the authentic backdrop.

Locations such as Belchamp Hall, standing in for Lady Jane’s Felsham Hall, are characters in themselves. The world is one of rural pubs, church fetes, country house auctions, and dusty workshops.

This setting creates a potent atmosphere of tradition and secrecy, where a priceless item might be found in a barn loft or a village junk shop. The show paints a picture of a parallel economy operating just beneath the surface of picturesque English life.

Origin Story

The television series Lovejoy was adapted from the popular novels by Jonathan Gash, the pen name of author John Grant. Developed for the screen by writer Ian La Frenais, it first aired on BBC One in 1986.

The initial series was produced by Television South (TVS) with Robert Banks Stewart as producer.

After a hiatus, strong viewer demand prompted its return in 1991, this time produced by the BBC. Across its six-series run, different producers guided the show, including Dick Everitt, Emma Hayter, Jo Wright, and Colin Shindler, with Allan McKeown serving as an executive producer in later years.

This production journey saw the show evolve while staying true to its core premise of a roguish antiques dealer.

Narrative Style & Tone

Lovejoy blends comedy and drama with a light, escapist touch. Episodes are typically self-contained capers or mysteries centred on a specific antique or fraud.

The tone is warm and humorous, avoiding graphic violence in favour of clever deceptions and character-driven banter.

A defining stylistic device is Lovejoy’s direct address to the camera. These confidential asides pull the audience into his confidence, explaining the intricacies of a scam or his assessment of a person.

This creates a unique narrative intimacy. The show is both a gentle procedural, educating viewers on the antiques trade, and a character piece about a charming operator navigating a world of greed and genuine beauty.

How is Lovejoy remembered?

Lovejoy is remembered as a quintessentially British comfort drama that achieved widespread popularity. It is credited with sparking a mainstream interest in antiques and the stories they hold.

Ian McShane’s charismatic, career-defining performance as the lovable rogue is its enduring centrepiece.

The show maintains a loyal cult following, with its East Anglian filming locations permanently dubbed “Lovejoy country” by tourism boards. It is seen as an affectionate, slightly romanticised portrait of rural English life and a niche trade.

While not a major awards winner, its longevity in repeats and fond retrospective discussions mark it as a reliable, well-crafted series that perfected a specific blend of crime, comedy, and countryside charm.

In Closing

Lovejoy endures because it offers a complete, inviting world. It pairs the intellectual puzzle of the antique with the human thrill of the con, all delivered with wit, warmth, and a uniquely charismatic guide at its helm.

Article word count: approximately 1450 words.