My Critique of Sherlock

Sherlock modernises the canon with visual bravura and brittle wit, but its bravado is double-edged. Benedict Cumberbatch’s precision and the show’s kinetic graphics create an arresting rhythm, yet narrative stunts, especially Reichenbach’s cheat, strain trust.

Compared to contemporaries like Line of Duty or The Missing, it prizes flamboyant puzzles over procedural rigour and sometimes substitutes spectacle for earned revelation. Later episodes hedge momentum with sentiment and convoluted arcs, magnifying sociopathic self-regard into a limitation rather than a flaw.

Nevertheless, the series matters: it mainstreamed deduction as spectacle, weaponised smartphones and launched a global template for modernised literary crime drama.

Principal Characters & Performances

Sherlock Holmes

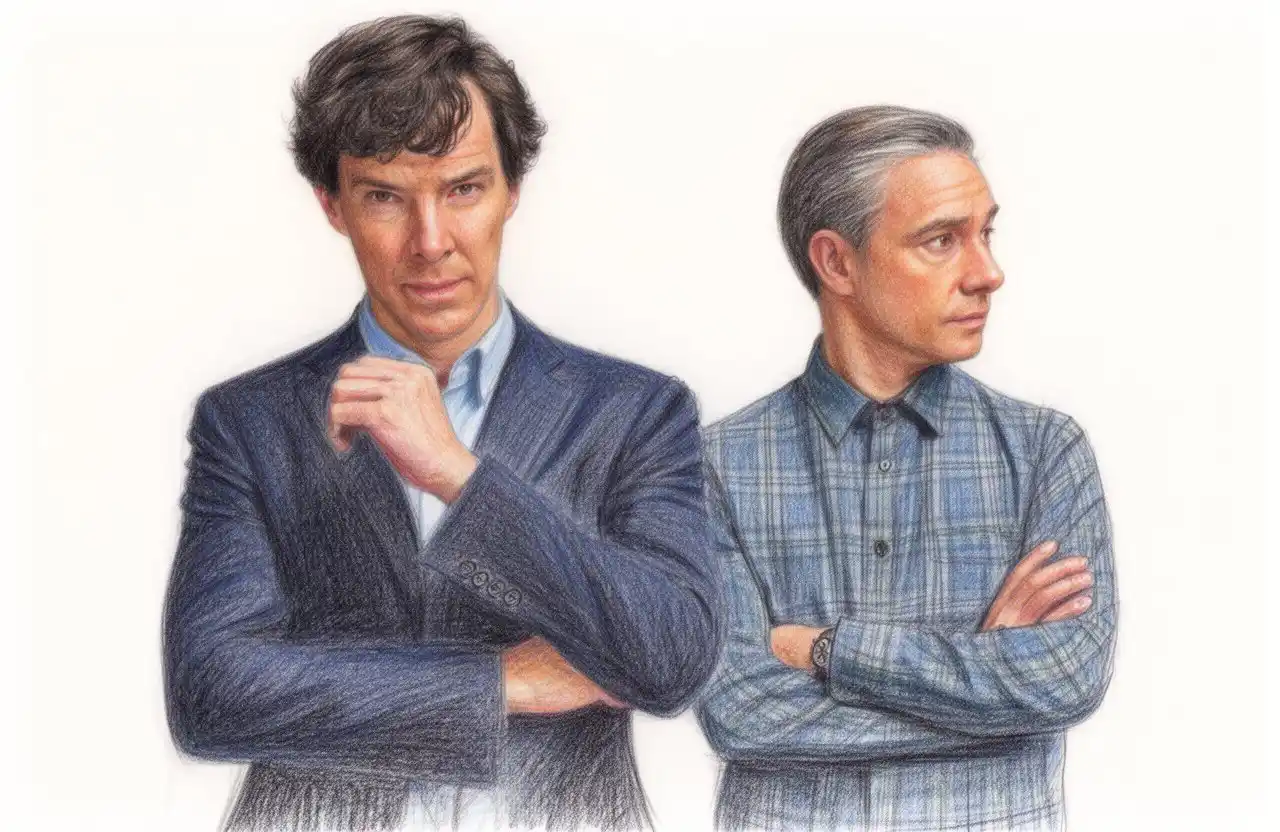

Benedict Cumberbatch’s Sherlock Holmes is the brilliant, abrasive engine at the heart of the series. He is a self-described “high-functioning sociopath,” a man whose mind operates at a velocity that leaves the ordinary world seeming dull and slow.

Cumberbatch captures the character’s intellectual arrogance and social impatience perfectly, but he also locates a profound, if deeply buried, humanity. This Sherlock uses a smartphone instead of a magnifying glass, texting his deductions and browsing the internet for clues.

His iconic coat and scarf become modern armour. The performance avoids mere eccentricity, grounding the genius in a tangible, sometimes painful, reality.

It is a portrayal that defined the character for a new generation, making the cold logic compelling and the rare flashes of vulnerability genuinely moving.

Cumberbatch charts a clear evolution from the detached consultant in “A Study in Pink” to a man who, by “His Last Vow,” is willing to sacrifice everything for his friends. This arc gives the series its emotional spine, proving that even the most brilliant mind can learn what it means to care.

Dr. John Watson

Martin Freeman’s John Watson is the essential counterweight to Sherlock’s whirlwind. A former army doctor grappling with the psychological aftermath of Afghanistan, he finds a new purpose and a different kind of adrenaline alongside Holmes.

Freeman brings a brilliant, understated naturalism to the role. His Watson is not a bumbling sidekick but a capable, courageous, and deeply loyal man.

He is the audience’s conduit, often exasperated but always steadfast.

The chemistry between Freeman and Cumberbatch is the series’ bedrock. Their banter provides much of the show’s humour, but their bond provides its heart.

Watson’s blog chronicles their cases, narrating their adventures to a public fascinated by the detective.

His relationship with Mary Morstan, played by Amanda Abbington, adds a crucial domestic dimension, forcing Sherlock to confront the complexities of human attachment. Freeman makes Watson the emotional anchor, ensuring the spectacle of deduction never loses its human stakes.

Notable Support and Guest Stars

The world around Sherlock and John is populated by a superb ensemble. Mark Gatiss, the series co-creator, plays Mycroft Holmes with delicious, icy omniscience, portraying a government power-broker whose sibling rivalry masks a twisted form of care.

Andrew Scott’s Jim Moriarty is a seismic presence. He reimagines the criminal mastermind as a chaotic, giggling agent of anarchy, a performance that is both terrifying and mesmerizing.

Una Stubbs provides warmth and wit as their long-suffering landlady, Mrs Hudson.

Louise Brealey’s Molly Hooper, the quietly smitten pathologist, undergoes one of the series’ most subtle and powerful character journeys. Rupert Graves embodies a pragmatic, weary Detective Inspector Greg Lestrade, the rare official who trusts Sherlock’s methods.

Guest stars like Lars Mikkelsen as the reptilian blackmailer Charles Augustus Magnussen and Phil Davis as the cabbie in “A Study in Pink” create memorable adversaries, each challenging Sherlock in uniquely personal ways.

Key Episodes & Defining Stories

A Study in Pink

This is where it all begins. The episode masterfully introduces Cumberbatch’s Sherlock and Freeman’s John, forcing them together as flatmates and partners to solve a series of mysterious suicides.

Phil Davis guests as the sinister cab driver.

Directed by Paul McGuigan and written by Steven Moffat, it establishes the show’s entire visual language: the on-screen text, the rapid-fire deductions, the sleek cinematography of modern London. It’s a statement of intent.

For the series arc, it lays the foundational relationship and introduces key players like Mycroft and Lestrade. Fans remember it for that electric first meeting at St.

Bart’s and the tense, philosophical showdown in a Bloomsbury laundry room.

It’s the essential starting point, proving that a deerstalker and a pipe are not required to capture the essence of Holmes and Watson’s timeless dynamic.

The Reichenbach Fall

This is the series’ most iconic cliffhanger, pitting Sherlock against Andrew Scott’s Moriarty at the peak of their war. Moriarty, in a performance of terrifying playfulness, orchestrates Sherlock’s public ruin, forcing an impossible choice.

Written by Stephen Thompson and directed by Toby Haynes, the episode is a masterclass in escalating tension. Guest star Katherine Parkinson plays the journalist Kitty Riley, whose reporting becomes a key weapon in Moriarty’s scheme.

It matters because it represents the ultimate test of Sherlock’s intellect and his friendship with John. The rooftop confrontation at St.

Bartholomew’s Hospital and its devastating aftermath became a global water-cooler moment.

Fans remember the agonizing suspense, the brilliant game of lies, and the two-year wait to unravel the mystery of Sherlock’s survival. It’s event television at its most powerful.

His Last Vow

The third series finale sees Sherlock confronting a different kind of evil: Lars Mikkelsen’s Charles Augustus Magnussen, a blackmailer who trades in secrets rather than theatrical violence. The stakes are intensely personal, threatening John’s wife, Mary.

Written by Steven Moffat and directed by Nick Hurran, the episode delves into moral ambiguity and sacrifice. Lindsay Duncan appears as Lady Smallwood, and Sherlock’s parents, played by Timothy Carlton and Wanda Ventham, add familial context.

It’s crucial for showing how far Sherlock will go to protect his “family,” culminating in a shocking act that changes everything. The episode is remembered for Mikkelsen’s chillingly calm villainy, the revelation of Mary’s past, and that stunning, game-changing final shot.

It demonstrated the series’ willingness to take massive narrative risks, pushing its characters to their absolute limits.

The World of Sherlock

The series transplants the essence of Conan Doyle’s London into the 21st century with remarkable confidence. The iconic 221B Baker Street is recreated as a cluttered, tech-filled flat above Speedy’s cafe on North Gower Street.

This is a city monitored by CCTV, connected by smartphones, and navigated by black cabs. Scotland Yard remains a constant, though often sceptical, presence.

The visual palette is cool and modern, from the glass of the London Eye to the sterile labs at St. Bart’s.

Yet, Gothic shadows still fall. The fog rolls over Dartmoor in “The Hounds of Baskerville,” and the spectre of Victorian London is vividly resurrected in the special “The Abominable Bride.” The world feels both recognisably our own and thrillingly heightened.

It’s a setting where a mind palace is as real as a police siren, proving that mystery and intellect are timeless, regardless of the era.

Origin Story

Sherlock was born from the shared vision of writers Steven Moffat and Mark Gatiss, both lifelong fans of Arthur Conan Doyle’s original stories. Their concept was deceptively simple: what if Sherlock Holmes and John Watson lived and solved crimes in present-day London?

Produced by Hartswood Films for BBC Wales, the journey began with a 60-minute pilot filmed in early 2009. The BBC, impressed but wanting more, took the unusual step of commissioning a full series of three 90-minute episodes instead.

The original pilot was reshot and expanded into “A Study in Pink.” This commitment to a feature-length format allowed the stories room to breathe and established the show’s cinematic quality from the very start, setting it apart from standard television drama.

Narrative Style & Tone

Sherlock is defined by its kinetic, visually inventive storytelling. It uses single-camera production to create a cinematic feel, employing rapid editing, graphic overlays, and on-screen text to visualise Sherlock’s racing thought processes.

The tone is a precise blend of gripping crime drama, intellectual puzzle, and character-driven comedy. The writing, led by Moffat and Gatiss, is sharp and witty, finding humour in the clash between Sherlock’s logic and social norms.

Episodes are structured like modern thrillers, often with complex, multi-layered plots that reward close attention. The musical score by David Arnold and Michael price is pulsating and iconic, underscoring both tension and triumph.

It never feels like a dry adaptation; it feels like a reinvention, buzzing with the energy and tools of the contemporary world while honouring the spirit of the source material.

How is Sherlock remembered?

Sherlock is remembered as a cultural phenomenon that redefined the television detective for the digital age. It achieved that rare feat of being both a critical darling and a massive ratings success, drawing over eleven million viewers at its peak in the UK.

Its impact was global, sparking intense online fandom and discussion, particularly around mysteries like the “Reichenbach Fall” survival. The performances of Cumberbatch and Freeman became definitive, earning BAFTAs and Primetime Emmys.

The show’s stylish modernisation influenced a wave of subsequent adaptations, proving classic characters could thrive in contemporary settings. Phrases like “high-functioning sociopath” entered the lexicon.

While its later series prompted debate, its legacy as a bold, brilliantly executed, and era-defining piece of television drama is secure. It made Sherlock Holmes feel thrillingly alive and relevant for a new century.

In Closing

Sherlock stands as a masterclass in adaptation, a series that honoured its literary roots while fearlessly carving its own iconic path. It remains a benchmark for intelligent, character-driven television.

{ “@context”: “https://schema.org”, “@type”: “TVSeries”, “name”: “Sherlock”, “description”: “Sherlock modernizes Holmes with kinetic visuals & Cumberbatch’s iconic “sociopath.” Brilliant deduction clashes with narrative stunts & spectacle, yet it landmarked modern crime drama globally.”, “image”: “https://www.acupofcrime.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/sherlock.webp”, “url”: “https://www.acupofcrime.com/tv/sherlock/”, “genre”: “British Crime Drama” }