My Critique of The Sandbaggers

The Sandbaggers remains the definitive blueprint for bureaucratic espionage drama, excelling in its unflinching procedural realism and talk-driven tension. Its defining strength is the stark portrayal of Whitehall’s political calculus, where resource scarcity and diplomatic fallout weigh heavier than any field operative’s skill.

However, this relentless focus on administrative attrition carries a notable constraint: the series can feel stagey and overly reliant on conference-room exposition to a modern eye. It decisively rejects the James Bond paradigm, exchanging glamour for the moral exhaustion of the Cold War.

For contemporary viewers, it matters as a masterclass in character-driven stakes.

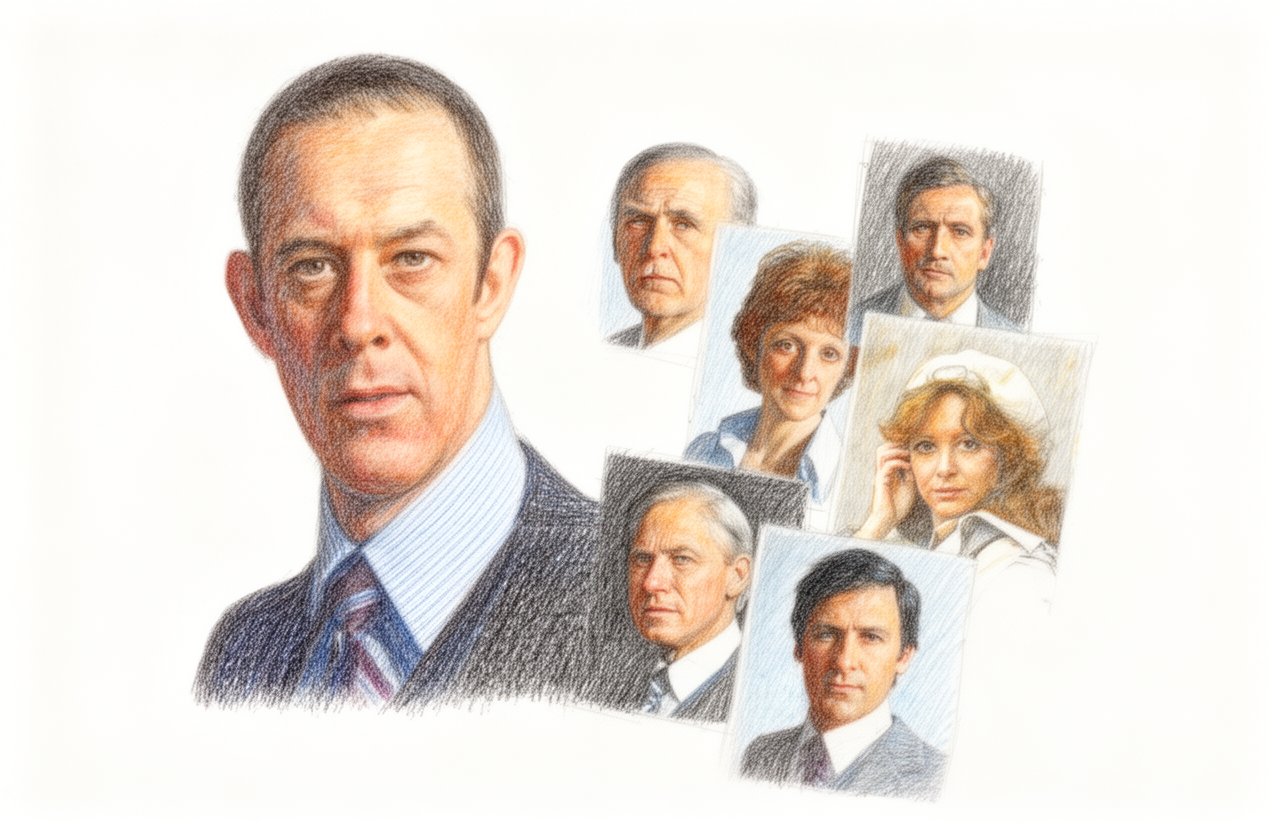

Principal Characters & Performances

Neil Burnside

Roy Marsden’s portrayal of Neil Burnside is the granite core of The Sandbaggers. As the Director of Operations for the Secret Intelligence Service, Burnside is a man perpetually at war on two fronts: against Britain’s enemies, and against his own government’s bureaucracy.

Marsden plays him with a chilling, controlled intensity.

Burnside is a brilliant strategist and a devoted patriot, but his loyalty is to the mission and his agents, not to political convenience. His cynicism is hard-earned, his humour bone-dry.

The performance is a masterclass in suppressed emotion. You see the weight of every decision in the set of his jaw, the slight narrowing of his eyes.

He is not a likable man, but Marsden makes him compellingly credible. His relationships are transactional, his personal life a shambles, yet his dedication is absolute.

This complexity makes him one of television’s most authentic and enduring intelligence figures.

Willie Caine

Ray Lonnen’s Willie Caine, callsign Sandbagger One, provides the crucial human counterpoint to Burnside’s icy calculus. Caine is the man in the field, the one who carries out Burnside’s often brutal orders.

Lonnen brings a weary professionalism and a palpable moral compass to the role.

Caine is a consummate operative, but he is no action hero. He is pragmatic, cautious, and deeply aware of the human cost.

His loyalty to Burnside is tested repeatedly, founded on a grudging respect rather than friendship. Lonnen excels in showing the strain of the job, the quiet dread before a mission, and the residual trauma afterwards.

The dynamic between Caine and Burnside is the engine of the series. Caine represents the conscience Burnside has had to bury to do his job.

Lonnen’s grounded, understated performance ensures the Sandbaggers themselves are never romanticised, but seen as skilled, vulnerable professionals.

Sir James Greenley & Matthew Peele

The upper echelons of SIS are defined by two superb performances. Richard Vernon’s Sir James Greenley, the Chief known as ‘C’, is the epitome of the old-school civil servant.

Vernon portrays him as thoughtful, decent, and often tragically caught between Burnside’s operational demands and political pressure from above. He is a buffer, not a barrier, and his eventual retirement leaves a void.

Jerome Willis, as Deputy Chief Matthew Peele, is the perfect bureaucratic foil. Peele is career-minded, risk-averse, and perpetually exasperated by Burnside’s maverick tendencies.

Willis plays him not as a villain, but as a man whose priorities are the smooth running of the office and his own advancement. His constant clashes with Burnside over protocol and budget are a central source of the series’ tension.

Jeff Ross & Supporting Figures

The transatlantic relationship is personified by Bob Sherman’s excellent performance as CIA London Chief Jeff Ross. Sherman plays Ross as a charming but ruthlessly pragmatic ally.

The friendship and rivalry between Ross and Burnside is a highlight, built on mutual respect and a clear understanding that national interests will always trump personal rapport.

Alan MacNaughtan brings gravitas as Sir Geoffrey Wellingham, the Permanent Under-Secretary and Burnside’s former father-in-law, embodying the political oversight that constantly frustrates SIS. Elizabeth Bennett, as Sandbagger Laura Dickens, leaves a lasting impact with her portrayal of a capable operative in a perilous world.

Key Episodes & Defining Stories

First Principles

The series opener is a mission statement in narrative form. When a British spy plane crashes in the Soviet Union, Neil Burnside must orchestrate a near-impossible extraction.

The episode immediately establishes the show’s DNA: tense, talk-driven strategy sessions in drab Whitehall offices replace action sequences.

We meet Burnside at war with his own side, battling Sir Geoffrey Wellingham and even his own Chief for the resources to save an agent. The introduction of CIA officer Jeff Ross sets the tone for a fraught ‘special relationship’.

This episode is essential because it defines the stakes. It shows that the real enemy is often time, bureaucracy, and political cowardice, not just the KGB.

Fans remember it for its ruthless subversion of spy genre tropes from the very first scene.

Special Relationship

This first series finale is arguably the show’s most devastating hour. The mission involves Sandbagger Laura Dickens crossing into East Berlin to secure a defector.

As the operation unravels, Burnside is forced into an appalling choice with fatal consequences. The title’s irony is brutal, highlighting the gap between diplomatic niceties and field reality.

The episode’s power lies in its emotional gut-punch and its lasting legacy. The death of a core character is handled without fanfare or heroics, a stark reminder of the show’s unforgiving realism.

This event haunts Burnside and defines his character for the remainder of the series. It is remembered not just for its plot, but for its profound statement on sacrifice and the true cost of intelligence work.

Operation Kingmaker

This episode masterfully shifts the battlefield from Eastern Europe to the corridors of Whitehall. With ‘C’, Sir James Greenley, retiring, Burnside engages in a covert campaign to influence the succession, fearing the wrong candidate will destroy the Service’s effectiveness.

It’s a brilliant study in bureaucratic intrigue.

Burnside manipulates allies, leaks information, and uses Willie Caine as a pawn in a political game. The episode showcases the series’ intellectual depth, proving that office manoeuvring can be as tense as any field operation.

It matters because it reveals Burnside’s ultimate motivation: preserving the institution he serves, even if it means undermining its current leadership. Fans prize it for its sharp writing and its insight into the unglamorous, power-driven heart of government.

The World of The Sandbaggers

The Sandbaggers exists in a world of greyscale morality and institutional drabness. This is the British Secret Intelligence Service during the late Cold War, a place of filing cabinets, cheap wood veneer, and endless cups of tea.

The grandeur of Whitehall is just outside the window, but inside the offices are functional and worn.

Operations are planned in these rooms, with maps and telephones, not with exotic gadgets. The field is not glamorous; it’s often wet, cold, and terrifyingly exposed.

The series meticulously builds this environment of mundane high-stakes. The relationship with the CIA is a constant negotiation, an alliance of necessity fraught with suspicion and competing agendas.

This world feels authentic because it is claustrophobic and paper-bound. Success is measured in small, fragile advantages, and survival often depends on a favourable minute in a committee meeting rather than a marksman’s bullet.

Origin Story

The Sandbaggers was the creation of Ian Mackintosh, a former naval officer turned writer. He drew on his background to craft a spy drama of unprecedented realism for Yorkshire Television.

Mackintosh wrote almost every episode, maintaining a singular vision.

Tragically, during production of the third series in 1979, Mackintosh disappeared when his light aircraft was lost over the Gulf of Alaska. His death cast a long shadow.

Additional writers were brought in to complete the final episodes, and the series concluded with an unresolved cliffhanger, the production team deciding it could not continue without its creator.

Narrative Style & Tone

The style of The Sandbaggers is deliberate and austere. It rejects the glamour of the James Bond franchise outright, favouring procedural detail and psychological tension.

Plots are driven by dialogue, by the subtle power plays in a conversation, not by chases or explosions.

The tone is realistic, morally ambiguous, and often deeply cynical. There is very little incidental music, forcing the viewer to sit in the silence of a difficult decision.

The humour is dry and born of professional exasperation. It presents intelligence work as a draining, ethically complex profession where good people are often broken by impossible choices.

How is The Sandbaggers remembered?

The Sandbaggers is revered as a cult classic, the thinking person’s spy drama. It developed a particularly fervent following in the United States through PBS broadcasts, with fans organising dedicated conventions.

Its reputation has only grown over time, introduced to new audiences through DVD releases.

It is remembered for its uncompromising realism, its superb character writing, and its willingness to confront the grim mechanics of statecraft. Critics and later creators, like comic writer Greg Rucka, cite it as a prime influence for its grounded approach.

The mystery of Ian Mackintosh’s disappearance adds a layer of poignant intrigue to its legacy. It stands as a benchmark for serious espionage storytelling, a definitive and peerless portrayal of Cold War intelligence from the inside.

In Closing

The Sandbaggers remains a high-water mark of British television drama. Its power lies in its intellectual rigour, its flawless performances, and its unflinching gaze into a world where duty demands the sacrifice of conscience, and sometimes, of lives.

Article word count: approximately 1250 words.