My Critique of Van der Valk

Van der Valk’s defining strength lies in its unsentimental gaze at Amsterdam’s underbelly, interrogating privilege with procedural rigour. Barry Foster’s commissaris, cynical yet humane, is anchored by a cool, location-heavy aesthetic; early studio-bound episodes occasionally stiffen, but the shift to 16mm with Euston Films tightened the visual nerve.

Its unvarnished treatment of class, gender and institutional pressure places it alongside the era’s grittiest British procedurals, while the ever-present city keeps it distinct. For modern viewers, it matters because it refuses glamour, letting moral ambiguity and procedural detail breathe without comfort or cant.

Principal Characters & Performances

Commissaris Simon “Piet” van der Valk

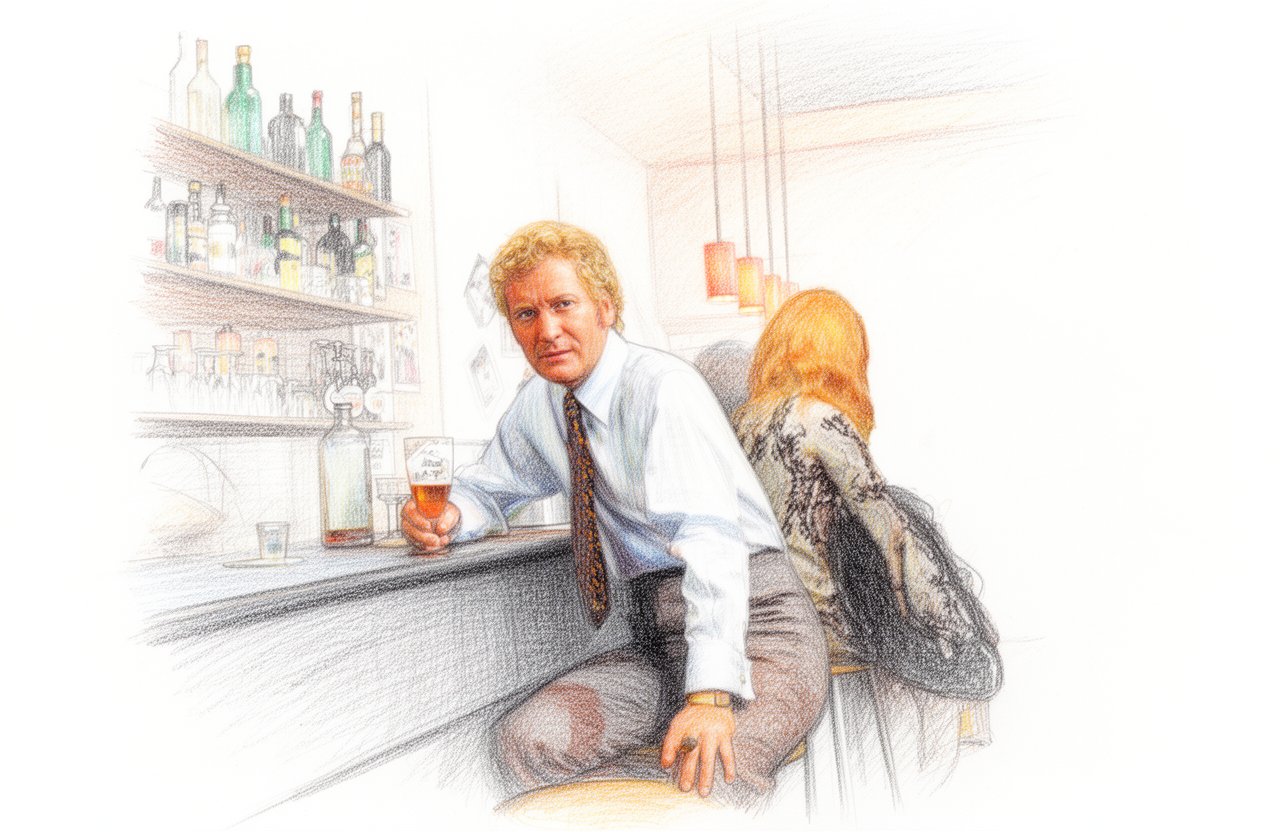

Barry Foster’s portrayal of the Amsterdam detective is the unshakeable centre of the series. He brings a world-weary intelligence to the role, a man who navigates the canals and backstreets of his city with a quiet, cynical authority.

This is not a detective given to flashy deductions or theatrical outbursts. Foster’s performance is built on observation and a deep-seated intuition about human frailty.

He often seems more at home with the city’s marginal figures than with his own superiors, his patience wearing thin with bureaucratic obstruction and political influence. Yet this cynicism is balanced by a fundamental, if well-hidden, compassion.

Foster ensures Van der Valk is never just a functionary; he is a husband, a colleague, and a man whose job constantly forces him to confront the darker seams of society, a burden he carries with a resigned but persistent sense of duty.

The character’s Dutch identity, played by an English actor, is sold entirely through Foster’s conviction. He creates a believable, grounded professional whose methods rely as much on understanding people as on forensic procedure.

This combination of instinctive intelligence and moral pragmatism, delivered with Foster’s understated charisma, made Piet van der Valk a distinctive and enduring figure in the landscape of 1970s television detectives.

Arlette van der Valk

The role of Van der Valk’s wife, Arlette, provides the essential domestic counterpoint to the grim world of police work, and was portrayed by three actresses across the series’ run. Susan Travers originated the part in the first two series, establishing Arlette as a perceptive and steadfast presence.

She is not merely a domestic backdrop but often serves as her husband’s moral sounding board, her perspective occasionally cutting through his professional detachment.

Joanna Dunham took over the role for the third series in 1977, bringing a slightly different but equally resilient energy to the character. This transition occurred as the production style shifted, but the core function of Arlette remained: to anchor Van der Valk in a world of normalcy and personal consequence.

Later, in the 1990s series, Meg Davies assumed the role, demonstrating the character’s enduring importance to the show’s dynamic.

Arlette’s presence is crucial. She represents the life and stability that Van der Valk’s work constantly jeopardises, both emotionally and, in episodes like “Enemy”, physically.

The relationship, portrayed with warmth and occasional friction, adds a layer of depth and vulnerability to the lead character, preventing him from becoming a mere crime-solving automaton and grounding the series in tangible human connections.

Notable Support and Guest Stars

The world around Commissaris Van der Valk is populated by a strong roster of supporting players who define his professional environment. Michael Latimer, as Inspecteur Johnny Kroon, provides a reliable and earnest foil in the early series, the diligent junior officer to Van der Valk’s experienced mentor.

The role of the overseeing hoofd-commissaris saw several actors, each bringing a distinct bureaucratic pressure.

Martin Wyldeck played Hoofd-commissaris Samson in Series 1, with Sydney Tafler as Halsbeek in Series 2. Nigel Stock then portrayed Samson in the third series, his performance capturing the tense balance between supporting a brilliant but troublesome detective and answering to political masters.

This rotating position of authority consistently presented Van der Valk with institutional obstacles to navigate.

Guest stars often filled the roles of victims, suspects, and witnesses, with episodes drawing on talented character actors to bring Amsterdam’s diverse citizenry to life. From wealthy bankers to petty thieves, these performances were key to the series’ social texture.

Later series also introduced Richard Huw as Wim van der Valk, the detective’s son, adding another dimension to the portrayal of the detective’s family life and the personal costs of his vocation.

Key Episodes & Defining Stories

A Death by the Sea

This opening episode of the second series immediately establishes the show’s core strength: a sceptical eye turned towards power and respectability. A wealthy banker’s story about his wife drowning unravels under Van der Valk’s quiet, persistent scrutiny.

The investigation peels back the veneer of Amsterdam’s elite, revealing a corrosive mix of money, privilege, and marital discord.

Fans remember it for crystallising the series’ morally uncompromising tone. Despite pressure from influential figures to drop the case, Van der Valk doggedly pursues the truth.

The cool, location-heavy visual style, with its shots of desolate beaches and austere interiors, is emblematic of Thames Television’s early 1970s crime output. It’s a perfect entry point, showcasing Barry Foster’s intuitive detective work and the show’s willingness to let a picturesque setting harbour very dark secrets.

Enemy

“Enemy” marks a dramatic turning point, not just in story but in the entire production ethos of the series. It inaugurates the third series with a tense, filmic car chase through Amsterdam, signalling the shift to full location shooting by Euston Films.

The episode personalises the danger of Van der Valk’s job like never before, as a vendetta from a criminal’s associate brings terror to his own doorstep.

The threat against Arlette, now played by Joanna Dunham, forces Van der Valk to confront the consequences of his actions beyond the solved case. It’s a landmark episode that marries psychological menace with procedural detail, redefining the show’s visual identity for the late 1970s.

The introduction of Nigel Stock as Chief Inspector Samson also sets a new dynamic of authority. Fans see it as the moment the series became more cinematic and personally intense.

A Man of No Importance

This episode from the second series exemplifies the show’s humane heart and its focus on social texture. The discovery of an anonymous dead man on a canal barge is a case many would dismiss.

Van der Valk, however, makes it a mission to restore dignity to the victim by uncovering his identity and story.

The investigation becomes a tour of Amsterdam’s underclass—boarding houses, casual labour, and overlooked lives. It’s a quietly radical premise for a police drama, insisting that every life matters.

The episode is a critical favourite for its unvarnished depiction of the city away from the postcard views and for demonstrating that Van der Valk’s motivation isn’t just about catching criminals, but about bearing witness to those society would rather forget.

The World of Van der Valk

Amsterdam is far more than a scenic backdrop in Van der Valk; it is a central character. The series uses the city with a dual purpose.

On one hand, it showcases the iconic visuals: the serene canals, the Magere Brug, the gabled houses along the waterways. These establish an atmosphere of historic beauty and order.

On the other hand, the stories delve into the city’s less picturesque corners. The red-light district of De Wallen, anonymous canal-side warehouses, and suburban villas in places like Aerdenhout become settings for crime.

The police environments shift from the Art Nouveau Politiebureau on Leidseplein in early series to the more modern headquarters on Marnixstraat later on.

This juxtaposition is key to the show’s identity. The familiar, almost tourist-friendly vision of Amsterdam is constantly undercut by the grim realities of the crimes investigated there.

The city becomes a landscape where respectability and corruption, wealth and desperation, public beauty and private vice exist in close, uneasy proximity.

Origin Story

Van der Valk began as a British television interpretation of a Dutch literary creation. The series was produced for ITV by Thames Television, based on the Amsterdam detective Piet van der Valk created by British novelist Nicolas Freeling.

The first two series were recorded in 1971 and 1972, using a hybrid production method common to the era.

Interior scenes were shot on videotape at Thames’s Teddington Studios in London, while the vital Amsterdam atmosphere was captured on 16mm film during location shoots. This blend gave the early episodes their distinctive look.

Executive producers like Lloyd Shirley oversaw the project, with producers including Geoffrey Gilbert. The stage was set for a crime drama that would derive its unique flavour from its transplanted, yet meticulously realised, setting.

Narrative Style & Tone

The narrative style of Van der Valk is straightforward, procedural crime drama filtered through a distinctively European sensibility. Episodes are typically self-contained investigations into serious crimes like murder, often involving drugs or sexual motives.

The tone is relatively gritty and grounded, avoiding melodrama in favour of a slow-burn focus on character motivation and social context.

This darker subject matter is famously contrasted by the upbeat, jaunty theme tune “Eye Level,” composed by Jan Stoeckart under the pseudonym Jack Trombey. The music creates an ironic counterpoint, a reminder of the normal world that exists alongside the criminal cases.

Van der Valk himself operates with a cynical intuition, often chafing against political pressures from his superiors, which adds a layer of institutional conflict to the straightforward mystery plots.

How is Van der Valk remembered?

Van der Valk is remembered as a durable and distinctive staple of British television crime drama, its twenty-year intermittent run from 1972 to 1992 a testament to its sustained popularity. Its legacy is anchored by two particularly strong elements.

First, Barry Foster’s definitive portrayal of the intuitive, world-weary commissaris established a detective archetype that felt both professional and authentically human.

Second, the series is inseparable from its Amsterdam setting and its phenomenally successful theme music. “Eye Level” became a cultural phenomenon in its own right, topping the UK charts in 1973 for the Simon Park Orchestra.

The show’s ability to blend picturesque location work with gritty stories left a lasting impression. This legacy is confirmed by DVD releases from companies like Network, its availability on streaming platforms, and the very decision to launch a successful remake in 2020, introducing Piet van der Valk to a new generation.

In Closing

Van der Valk endures because it pairs a compelling, human detective with a vividly realised world, proving that the most intriguing mysteries are often about people and place as much as plot.